As Afghanistan’s cricket team continues its meteoric rise to the peak of international cricket, it finds itself subject to heavy politicisation.

International sporting competitions are exciting spectacles. Sporting contests mark rare periods in which politics, as a domain, finds itself relegated to the excitement and unpredictability of elite-level athleticism. Accompanying the whirlwind of excitement is the euphoria of national pride that finds itself squarely at centre stage.

Afghanistan and its recent cricketing success are no exceptions. The country’s political spectrum is indeed fractured and Afghans, both at home and abroad, may be divided. Yet a shared sense of optimism has coalesced around the cricket team. The team’s successes have been celebrated by figures and blocs straddling the political divide, including the governing Taliban. Government-affiliated figures, in particular the powerful Minister of Interior, Khalifa Sirajuddin Haqqani, have been quick to offer their congratulations and benefit from public proximity with the wildly popular cricketers.

Afghan Cricket: A Beacon of Unity?

The celebration of the team’s successes, though, has hardly remained exclusive to the Taliban. Even Taliban opponents, including avowed foe and former Vice President Amrullah Saleh, commended the team for its recent victory over Pakistan. Deferring to his strident opposition to the Taliban, Saleh heaped further, and markedly political, praise on the team. The team had, Saleh claimed, admirably remained aloof from politics and maintained a distance from the Taliban which, most crucially, was evidenced by their perceived rejection of the Taliban’s white flag. Between Amrullah Saleh’s lavish praise and being congratulated alongside Khalifa Sirajuddin Haqqani, the cricket team found itself being pulled from either side of an unending political tug of war.

The irony is that the tug of war is concurrent with the opposite reality of the team constituting the nucleus of a rare consensus. Everyone wants a piece of, and to be associated with, the team. Irrespective of political allegiances, the cricket team is an illuminating icon of national unity and pride. Unity, however, is not the same as unanimity. Amidst the adulation of the cricket team, a vocal group of Afghans, primarily on social media, have been vociferous in criticising the team, primarily due to their perceived proximity to the Taliban. This was largely in the aftermath of pictures with Taliban figures, the popular response to which has been divided. Some have hastily and angrily claimed them as irrefutable proof of the team’s support for the Taliban. Others have been more sympathetic; the team, many argue, can hardly afford to estrange those governing the country and thereby facilitating its travels and successes.

Afghan women’s rights activist Marzieh Hamidi has emerged as the cricket team’s principal critic. Hamidi, an Iranian-born and heavily Iranian-accented Afghan woman now based in France, has been brazen in her criticism of the Taliban. As far as recent developments were concerned, the outspoken Hamidi went as far as, potentially libellously, decrying the cricket team as ‘representatives of terrorism.’

Whilst diagnosing Hamidi’s vitriol toward the Pashtun-dominated cricket team remains largely guesswork, her X profile, in which her activism is centred, provides clues. With her anti-Taliban activism primarily centred on her X profile, the platform also features her usage of Tajik ethnonationalist terminology such as ‘Afghanistani.’ Her X profile also features her reposting quotes of fringe ethnonationalist figures like Latif Pedram.

Afghan Cricket: a Foreign Sport?

For many in Afghanistan, the successes of the Afghan cricket team are not mere causes for a shallow national pride. The team represents much else, and its success resonates at a far deeper level. The team’s victories are symbolic of a greater national character forged by, in no small part, an indomitable resilience in the face of the upheavals of the previous decades. Indeed, the wider Afghan tale of the past decades finds itself reflected poetically in the story and fortunes of the Afghan cricket team. It is a tale of displacement, Pakistani exile, establishment and eventual success so unexpected that it happened almost by accident. The first Afghan cricketers grew up with neither the amenities freely available to their soon-to-be international counterparts and nor, at least initially, with a lofty vision or specific goals. They were the desperately bored children of refugee camps scattered across the Durand Line in neighbouring Pakistan, whose parents had sought refuge first from the Soviet Union and later from the fallout of its withdrawal and collapse.

Together with its impoverished roots, the journey of cricket in Afghanistan, even by its gruelling local standards, was far from smooth. Attempts at promoting cricket had first been made during the royal era in the early 20th century, however the sport’s appeal was heavily dampened by associations with the widely disliked imperial power: Britain. By the post-2001 era, this prejudice had further hardened. The stain on the sport’s image had only been reinforced, this time through association with Pakistan: not just labelled as a British brainchild and successor state, but widely unpopular due its role in Afghanistan since 1978.

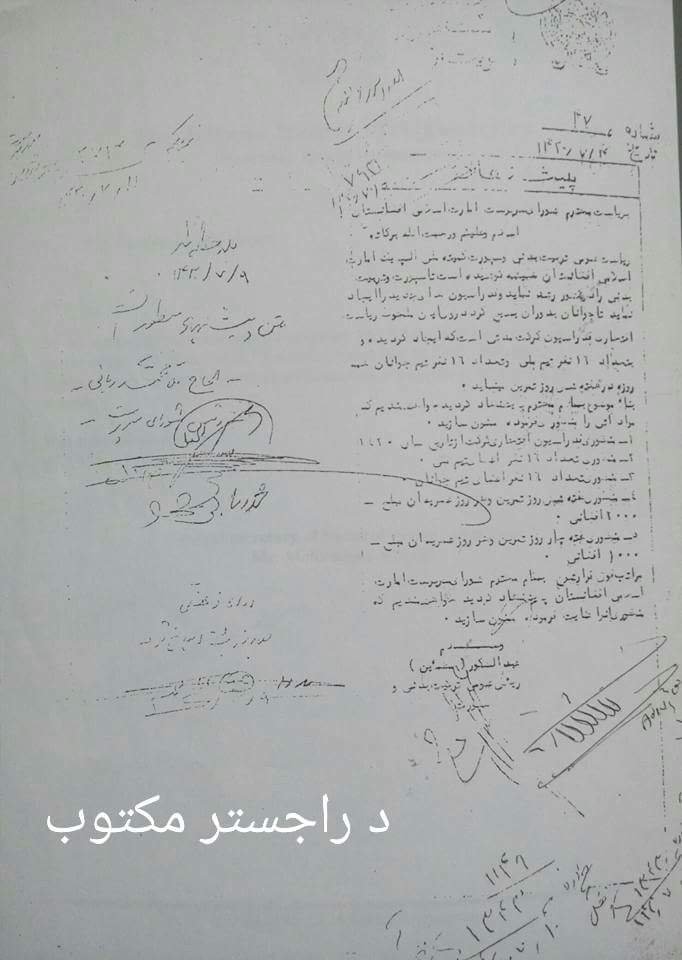

Ahmad Shah Pakteen: an Afghan umpire member of the International Panel of ICC Umpires, recalls distinctly the sport’s challenges. ‘People thought [cricket] was a foreign, and especially Pakistani, sport,’ Pakteen retells. That association was also caused by from the Taliban, then widely seen as a Pakistani proxy, who had enthusiastically attempted to promote the sport in the late 1990s. The Taliban’s Prime Minister, Mullah Muhammad Rabbani, had expanded the remit of the Afghan Cricket Federation in 1999. With Allahdad Noori as President, the Federation had managed to gain Affiliate Membership of the International Cricket Council by June 2001, mere months prior to Afghanistan’s invasion by the US and the toppling of the Taliban. ‘Cricket was [therefore] not viewed positively in Afghanistan,’ Pakteen stated. The brunt of political division was, and remains, borne by Afghan cricket.

Notwithstanding politically-rooted bigotry against the sport, Afghan cricketers marched boldly forth, undeterred by the occupation and accusations of playing a foreign sport. It was only a matter of time that the team’s increasing renown started gaining attention at the highest levels of government in the post-2001 era. Eventually, a specific fund was allocated to the newly-established Afghanistan Cricket Board (ACB), and training facilities started propping up across the country’s provinces.

Afghan Cricket’s International Rise

The team’s first appearance in an international competition came in the Asia Cricket Council’s 2004 Trophy. By 2015, the team had made it into the World Cup. Whilst entry into the World Cup was a massive step forth, Afghanistan was knocked out in the opening round. Progress remained undeniably on track. In 2017, only thirteen years after its debut into international cricket, Afghanistan was unprecedentedly awarded a full test membership. It marked the climax of a rapid journey from affiliate membership to full member status in less than two decades. Not long after, in 2023, the Afghan team defeated England: defending champions. The team’s stunning and rapid rise, for Pakteen, was hardly surprising; ‘God Almighty,’ he says smilingly, ‘gave Afghans a special talent in cricket.’

In the latest international tournament: 2024’s ICC T20 World Cup, Afghanistan reached the semi-final. Whilst a trophy again eluded the team, their success was nonetheless celebrated by millions across the country, especially the young, and embodied the narrative of a perseverant national pride. It is not surprising that cricket has emerged as the country’s most popular sport in less than two decades.

Afghan Cricket under the Taliban

Notwithstanding its rise, the team, as an inadvertent reflection of the Afghan story of the past decades, again suffered directly due to Afghanistan’s more recent political challenges. This time, these resulted from the upheavals stemming from the Taliban’s 2021 takeover, which led to the reestablishment of their Islamic Emirate. This time, the team and the ACB were no longer grappling with mere bigotry at home. In many respects, they were confronted by their greatest ever test, which was wholly divorced from sport itself. What was once a largely sympathetic and supportive international environment was now replaced by suspicion, apprehension and even disdain.

The ACB, would become the latest to find out that, contrary to the oft-repeated adage, sports is seldom separate from politics. In this, Afghanistan found itself with rare company. Political ramifications on sport have been prominent in recent years; the Russian football team found itself similarly penalised in the aftermath of Moscow’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and, at a more dispersed level, numerous footballers in top-flight football across Europe found that their condemnation of Israel’s massacre in Gaza would have consequences for their careers.

Much like others, the ACB would soon find out that those pointing the finger are also seldom free of blemishes. The ACB’s foremost critic was Australia. Although a cricketing giant, Australia’s own track record in Afghanistan held a grim irony. Australia remains confronted by numerous charges of war crimes committed during the NATO occupation of the country, in which Australia was an active participant. The recent stripping of medals from Australian commanders implicated in the atrocities points to potentially wider guilt, together with Australia jailing the whistleblower who brought the issue to attention. The Australian team, nonetheless, even cancelled its T20 match against Afghanistan due to explicit government advice warning ‘that conditions for women and girls in Afghanistan are getting worse.’ These included what is alleged were restrictions on female cricket participation.

Taliban policy toward female participation in sports is characteristically unclear. Any such policy, moreover, would hardly fall within the ACB’s remit. Whilst female sports has long been lacking, this can hardly be attributed solely to Taliban policy; it is a phenomenon that needs to account for the wider contours of a reactionarily conservative society. In retrospect, it is difficult to see why such reactionary conservatism wouldn’t be pervasive, having been inflamed by two decades of cynical tokenising women to garner legitimacy for what was, in word and deed, a foreign occupation. In an honour-based, religious, and patriarchal society, the association between women and sports would find itself inevitably tainted. Even sports stadiums were not spared as venues for female singers, dressed in locally frowned upon and ‘figure-hugging outfits’, to put on musical performances. The fact that music is also widely considered as religiously prohibited hardly helped, and the meagre returns of playing with fire, ultimately, were made clear in the death threats such actions provoked.

New and Turbulent Beginnings: Naseeb Khan’s Leadership

As the ACB adjusted frantically to the Taliban’s takeover, it learnt on the job. It focussed on shielding the national cricket team from the repercussions of the country’s upheavals. The burden of stabilising the country’s cricketing sector fell on the young shoulders of the Afghanistan Cricket Board’s new and Taliban appointed CEO: Naseeb Khan. Khan shared much with the cricketers; he too was young, a passionate enthusiast of the sport and had spent his early life as a refugee. A writer and poet by trade, he later graduated with a masters in Media and Mass Communication from the International Islamic University, and was also a prominent activist against the occupation who authored the Pashto book ‘Free Nation, Occupied Homeland.’

Being thrust into his new role, especially under the given circumstances, was a shock. His tenure of the past three years has largely been shaped by his attempts at navigating the ACB’s difficult path in representing a diplomatically isolated country in the unwelcoming and politicised arena of international sports. ‘The situation was chaotic [and] challenges were immense,’ Khan recalled. These ranged ‘from political instability,’ at home ‘to logistical nightmares,’ abroad. These logistical nightmares included Afghanistan, in the aftermath of the Taliban’s takeover, falling victim to crippling international sanctions.

The sanctions debilitated its financial sector and essentially cut off the country from international banking. To ameliorate this, the ACB, with Khan at its helm, hastily set up foreign bank accounts to ensure timely payroll for players and coaches. Sanctions notwithstanding, the end of the US occupation landed a further deadly blow to the country’s economy, whose fragility and reliance on now-miniscule foreign aid was laid unflatteringly bare. That sharp economic contraction would lead to an inevitable shortfall in the revenue of an already strained ACB, prompting a frantic round of engagement and negotiations.

Commercial relations were slowly established with a host of local and international companies. As the ACB’s ship slowly steadied, it focused on increasing activity. Its budget on membership fees were raised, playing fees for domestic players were increased by 300% and contract categories by 40%. The number of top flight (first class and List A) games were increased by 50%, together with holding domestic competitions such as the Green One Day Afghanistan and Qosh Tepa National T20 Cup. Eventually, performance-related bonuses were introduced. A High Performance Centre, staffed by foreign and domestic coaches, was established to further boost player performance.

Renormalisation and the Path Forward

With the initial challenges out of the way, the cricket team’s international success and preparations for the resumption of the Afghan Premier League (APL) in 2025 now being made in earnest, Khan is jubilant. ‘We managed,’ he says, with a wide grin, ‘to navigate through those chaotic times.’ His optimism is not unfounded. The cricket team, under his stewardship, has continued competing on the world stage and also reached new feats, as evidenced in Afghanistan’s reaching of the 2024 World Cup’s semi-final.

Yet due to circumstances out of its control, the cricket team still operates in the arena of increasingly global politics. Politics, per the adage, is the art of compromise, and the compromise allowing the Afghan team’s continued international participation may have been awkward, but it certainly worked. The cricket team of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan would compete, increasingly successfully, under the flag and to the blaring anthem of the now-defunct Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Little else can better signify the team’s awkward position.

Going forward, and success notwithstanding, the cricket team’s attraction of scrutiny inflaming of tensions is unlikely to subside. Internationally, through no choice of its own, its unenviable status is one of an international representative of the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate. Domestically, amidst wider political tussles and infighting, it is a victim of its own success. It is the shining national icon of whom everyone wants a piece: watched by all, adored by many, and criticised vociferously by some.

From the lens of sport, the future looks less gloomy. Both Pakteen and Khan anticipated the resumption of the Afghan Premier League in 2025 and eventual hosting of international matches in Kabul. With the ACB ship steered with increasing confidence and competence by CEO Khan and cricketing legend now Chairman Mirwais Ashraf, Pakteen is brimming with confidence. The confidence is rooted in the exemplary management of the ACB. ‘There has been no political interference,’ Pakteen asserted confidently, from the Taliban [government] in cricketing affairs.’

‘Cricket is more than just a game,’ Khan concluded. ‘It’s a rare source of national pride. It demonstrates what we [can] achieve through perseverance and passion.’