President Biden’s unilateral decision to break the Doha Agreement places an already precarious Afghan peace process under further strain.

The Afghan Peace Process has been a long-winded series of proposals, counter proposals and political posturing. An attempt to reinvigorate what seemed like a stale peace process, US Secretary of State Blinken wrote a letter to President Ghani proposing a conference to be held between different Afghan factions in Istanbul. The reasoning for this, at face value, was obvious. Turkey, as a majority Muslim state with whom Afghanistan had shared historically warm relations, was viewed positively across Afghan socio-political spectrum. The change in venue could breathe new life into a process seemingly at a gridlock in Doha.

The Inception of the Peace Process

The Afghan peace process technically started in 2013, when the Taliban political office in Doha was, amongst much controversy, formally unveiled. It was under the Trump Administration, however, that the peace process really gained momentum. The Trump Administration initially followed a campaign of maximum pressure aimed at breaking the resolve of the Taliban and their battlefield superiority. Violence and civilian casualties surged, reportedly by 330%. An opaque nexus of CIA-backed militias together with US troops carried out numerous night raids across the country. Aerial bombardments reached new heights, including the detonation of the Mother of All Bombs. Still, however, the Taliban held on, in some cases even gaining territory. Ending the war was one of President Trump’s key campaign promises, and realising the US could not meaningfully hope to defeat or even dent the Taliban militarily, a different approach was adopted.

The Trump Administration started engaging with the Taliban political office in Qatar in earnest, and directly. This was done according to the long-term demands of the Taliban: that any political settlement be first based on an agreement ensuring a US withdrawal, following which different Afghan factions could hammer out an agreement between themselves. As far as previous Washington policy was concerned, President Trump’s decision to negotiate directly with the Taliban was a break. Previous US policy had stressed the need for any settlement to include the government in Kabul: the claimed embodiment of the Afghan people’s sovereignty and democratic choice.

Kabul’s Crisis of Legitimacy

In acquiescing to the Taliban by speaking to them directly, Trump, as Ghani’s ally, delegitimised Ghani’s government beyond anything the Taliban could have hoped, by extension vindicating Kabul’s foes. Domestically, Trump engaging the Taliban meant that an already impotent Afghan government was faced with a further blemish domestically on a legitimacy it had always struggled to attain. After all, if the Afghan government were truly sovereign and not a puppet regime, why was a foreign power, that happened to be its main patron, negotiating with Kabul’s most powerful opponent in Qatar, in Kabul’s absence? This only further compounded Kabul’s crisis of legitimacy, stemming from the fact that it was borne of a foreign invasion in a country and amongst a people whose very national identity had been carved through resistance to previous invasions and occupations.

Still, however, Ghani was not a finished force. Not being party to the Doha Agreement, he refused to comply with the prisoner exchange it mandated, the culmination of eighteen months of negotiations in Qatar between US Special Representative Zalmay Khalilzad and the Taliban. This delayed the intra-Afghan negotiations, due to have started on March 10th 2020, by roughly 6 months, with Ghani attempting to regain some sliver of authority by stating that prisoner exchanges were his, and not Khalilzad’s prerogative. Whilst symbolic, this had practical ramifications. Ghani delayed the onset of intra-Afghan negotiations and also faced a backlash domestically. His actions seemingly proved to many spectators that not only was Ghani adopting an anti-peace platform, but that he saw his political demise in a peace deal most likely to replace him. Ghani only further reinforced this notion when he later angrily protested against ideas of an interim government.

The Peace Process Thus Far

Push and shove as he tried, Ghani was eventually strong-armed into abiding by the tenets of the Doha Agreement. The entirety of the prisoners were exchanged, and intra-Afghan negotiations were launched expeditiously. Yet they failed, not entirely unexpectedly, to yield anything meaningful. The negotiations commenced in bad faith, as Ghani’s reluctance to abide by the Doha Agreement sullied any potential goodwill between warring compatriots. The Taliban, already accustomed to fighting whilst negotiating, were accused of increasing violence. They in turn accused the government of provoking violence and, more importantly, using delaying tactics to benefit from a potentially more generous approach from an incoming Biden administration.

Changing Administrations

The Biden Administration has been far less concrete than the Trump Administration ever was. It took weeks for any official statements to be made, after which a letter from Secretary Blinken to Ashraf Ghani detailed plans for a 90-day Reduction in Violence, as well as plans for the upcoming, yet to be determined Istanbul Conference. The tone was softer but the position consistent: Ghani was being instructed and even threatened, with Blinken stating bluntly that all options, including the May 1st troop withdrawal, were on the table. Biden remarked that adhering to the May 1st deadline for the withdrawal of US troops would be ‘hard to meet’, later announcing that a complete withdrawal of US troops would be complete by September 11th 2021.

The Taliban

The Taliban, for their part, were and are vocal in what they term the ‘full implementation’ of the Doha Agreement, which stipulated the May 1st deadline for troop withdrawal. The Doha Agreement was a step forward insofar as it abandoned the insistence on the theoretical primacy of the Afghan government, adopting a pragmatic approach toward achieving peace. The Agreement, however, now poses its own problems in that it acquiesced to key Taliban demands which a succeeding US Administration is now hesitant to follow through on. Nor can it be assumed that the Taliban were consulted in what was evidently a unilateral extension of the deadline by the White House, based on the insurgents’ reaction. In the uncertain runup to Biden’s announcement of the deadline’s extension, Taliban spokesman Muhammad Naeem Wardag had announced that the group would not attend the Istanbul conference, due then to be held on April 16th, and added the issue was under further review by the team. This position remained unchanged, with the Taliban seemingly able to stave off what was reported as heavy Pakistani pressure to attend the conference. The conference was further postponed to mid-May, at the end of the holy Islamic month of Ramadan.

The Road to Istanbul

Based on their markedly negative reaction it can be deduced that it was highly unlikely the Taliban approved of or were even consulted regarding Biden’s unilateral September deadline. Recent surges in violence in Afghanistan, then, follow a logical course. Intra-Afghan negotiations, aimed fundamentally at reducing and ideally eliminating violence, were contingent solely on the Doha Agreement. The Doha Agreement now stands broken, and with the course of events now operating outside the Doha Agreement’s parameters, the emphasis on negotiations and lofty conferences is resultantly misplaced. The White House’s new, unilaterally declared deadline torpedoed the circumstances under which dialogue and negotiations could materialise, heavily contrary to its avowed aims of accelerating what was a slow peace process, but a peace process nonetheless. It instead incentivised the path of war, as the Taliban mount offensives around their strongholds in Ghazni and Helmand.

Looking forward to the Istanbul conference, assuming it is held, the odds of a fruitful diplomatic exercise remain bleak. For the Taliban, participation would come only with concessions before September, or after a US withdrawal is complete in September. By September, according to the current course of events, they would be able to press their military advantage, with little to deter them, to change the reality on the ground. Kabul, for its part, would partake in the conference in much the same manner as its previous undertakings in the peace process: divided, delegitimised, pushed and shoved by its patron in Washington. The complications with which the Biden Administration have placed the Taliban leadership and its resultant reaction would provide ample reason for Kabul to continue its demonstrable reluctance in the peace process, with added justification.

In placating neither side and paving a path where both gain more through the battlefield than on the negotiating table, the White House paves the path toward conflict with much ease, demonstrating for the umpteenth time the volatility and lack of wisdom guiding US diplomacy. Or lack thereof.

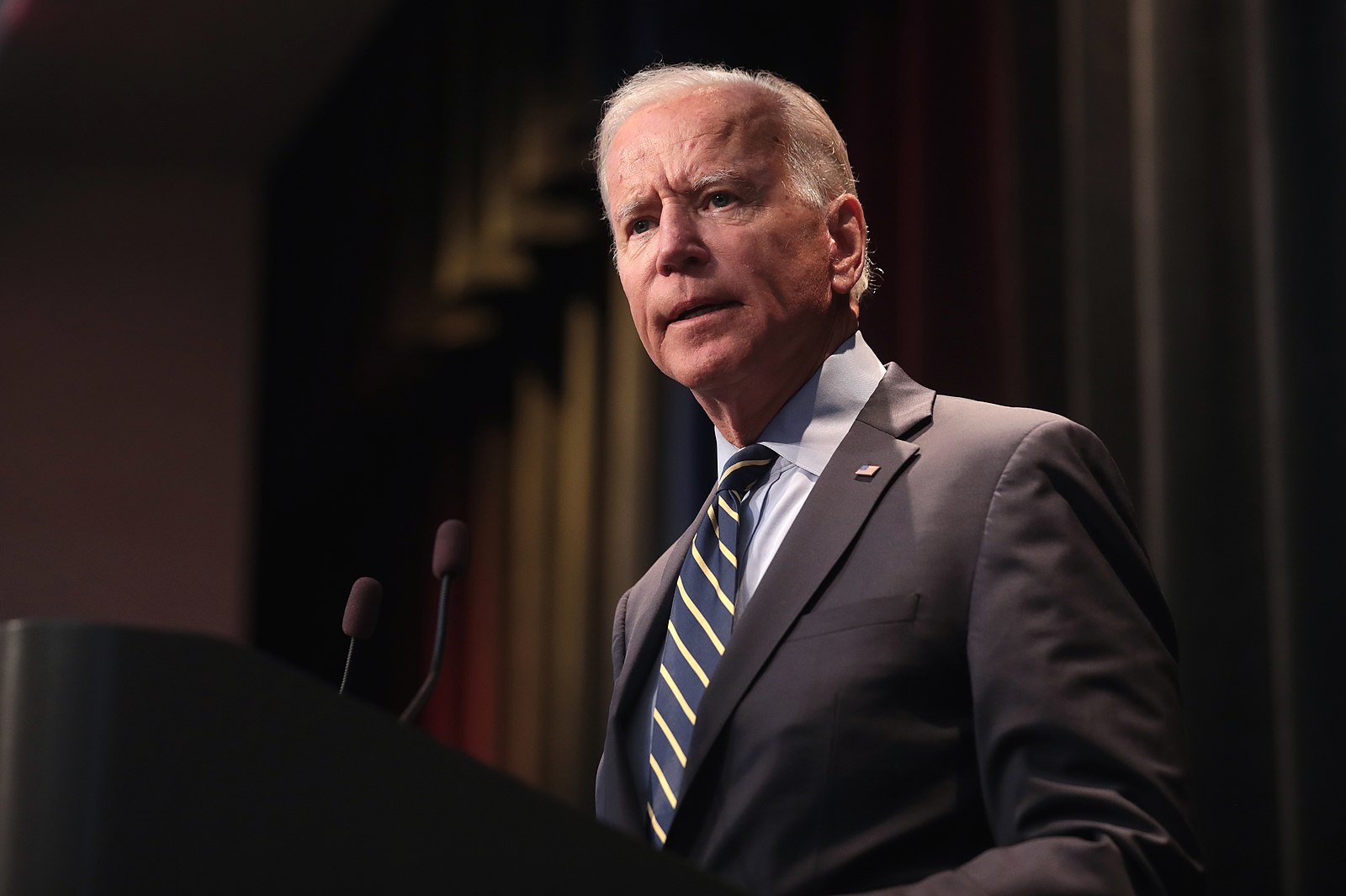

Photo: Gage Skidmore from Peoria, AZ, United States of America